- Topics

- Campaigning

- Careers

- Colleges

- Community

- Education and training

- Environment

- Equality

- Federation

- General secretary message

- Government

- Health and safety

- History

- Industrial

- International

- Law

- Members at work

- Nautilus news

- Nautilus partnerships

- Netherlands

- Open days

- Opinion

- Organising

- Podcasts from Nautilus

- Sponsored content

- Switzerland

- Technology

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom

- Welfare

Following on from other seafarer fatigue studies, the UK government last year commissioned Loughborough University to investigate the situation in the ferry sector. Dr Wendy Jones explains how the research was conducted – and what she and her colleagues found out

Previous research has identified fatigue to be a challenge in seafaring. For example, Project Horizon was a laboratory-based study which found high levels of sleepiness in seafarers. Particularly, it identified that split shifts adversely affected performance – and that being disturbed when off-watch increased sleepiness.

Project Martha was a long-term study of deep sea seafarers. It found risks to be particularly high for captains and night watch keepers, and that port work was more demanding than being at sea. However, relatively little research has been carried out in ferry operations.

Sleep is a biological need, and it is to be expected that every person will become sleepy every day. Risk occurs if people are fatigued while undertaking a safety-critical task. The longer it has been since a person last slept, the more pressure their brain will be under to sleep, and the ability to maintain wakefulness fluctuates across the day with the circadian rhythm. Shift work is most challenging if people are working at times when the circadian rhythm is not prompting wakefulness, and if it is difficult to get good quality sleep.

Focusing on ferries

Those working in the ferry industry may be at particular risk of fatigue because shift work is unavoidable. A wide variety of working patterns are used to meet the practical and commercial demands of operations. With 37,000 crossings each year into or out of UK ports, this is a potentially high-risk part of the sector. For example, in 2022, 41 people were injured, some seriously, when the roll on/roll off ferry Alfred ran aground in Scotland after the master fell asleep while navigating close to shore.

The UK Department for Transport (DfT) commissioned research to improve understanding of the risk that fatigue creates for seafarer wellbeing and vessel safety in ferry operations and explore how the impact could be reduced.

The research was led by Professor Ashleigh Filtness, an expert in sleepiness and fatigue who is part of the Transport Safety Research Centre at Loughborough University. The TSRC has a 40-year history of conducting research into all aspects of safety in transport. For this study, Loughborough University partnered with The Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute (VTI), an independent and internationally prominent research institute in the transport sector with particular expertise in measuring sleep and alertness.

Designing the research

The priority when designing this research was to hear the voices of seafarers, making sure that a wide range of people in many roles and from many operators had an opportunity to contribute. As a result, a wide range of methods were used, including subjective approaches (people's opinions and experiences) and objective measurement (how much sleep people get; how alert they are at work). The five research strands were:

workshop – a discussion with representatives from ferry operators to explore how rosters and shift patterns are designed, and how mathematical models could be used to compare different working arrangements

survey – open to anyone working in any role in participating ferry operators; 446 seafarers took part

focus groups – discussions with small groups of customer-facing staff; 45 people took part. Participants were mostly OBS, and also some ABs

interviews – with 11 masters and bosuns

field trial – 63 seafarers wore FitBit watches for four weeks, assessed how sleepy they felt at work, and tested their reaction times to assess alertness

Our main conclusion from this research was that fatigue in the ferry sector is a significant issue which does cause accidents. Below are some notable findings that we are keen to publicise throughout the industry.

Fatigue is widespread on ferries

Fatigue was an issue in all job roles and shift patterns. It affected crews living onboard ferries and those who went home to sleep between their shifts.

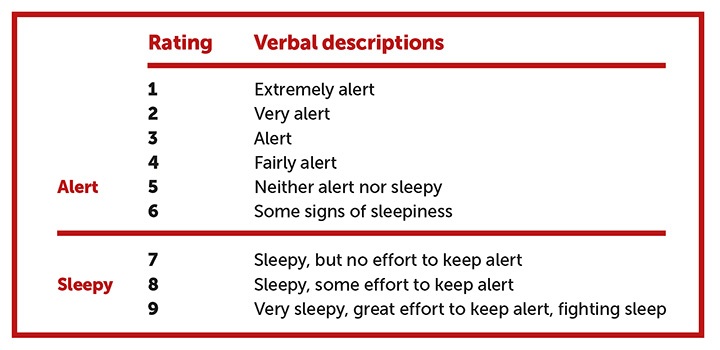

In total, 18% of survey respondents had fallen asleep at work at least once in the last 12 months, and 59% said that at least once a month they had to fight sleepiness at work. When alertness was monitored in the field trial, around one quarter of measurements showed respondents to be sleepy at work (scoring 7 or higher on the Karolinska Sleepiness scale – see Figure 1).

One impact of this fatigue is accidents – 31% of survey respondents reported having had one or more fatigue-related incidents in the last 10 years. The majority (85%) did not think that their employer would know that fatigue was a factor.

Fatigue is a multi-faceted problem

The comments from survey respondents and workshop participants revealed that seafarers are fighting fatigue on ferries for several different reasons.

Long hours and shift variability: Long working hours, varying shift start times and moving between day and night shifts were reported as causing particular problems. Some seafarers had working hours which were much longer in the summer than winter. Some reported that they frequently worked beyond their scheduled shift time (e.g. if sailings were delayed) or that their working patterns or rosters were often changed and that this increased fatigue. Evidence from the field study showed many participants' working hours that were different from the original roster.

'A straight shift comprises of 13-hour day with 2 half hour meal breaks and split shift comprises of 6 hour on 6 hours off with no meal breaks for a 2 week on 2 week off rota'

Interrupted sleep: Senior staff on live-onboard vessels could be disturbed when off duty, particularly where they were the only person on the vessel working in that role. For all crew types, training drills could conflict with crew rest time, although attempts were generally made to minimise this.

'I work permanent nights, 8pm to 8:30am; I have a break between 2:30 and 4:30am. Drills take place at 18:30 hours once a week and impact on my sleep time'

Rest does not equal sleep: Poor sleep quality and lack of sleep were major challenges. Only 21% of survey participants reported their sleep in the last three months as being good or quite good.

For live-onboard crew, sleep quality was adversely affected by noise (other crew, passenger announcements), heat, cold, vibration and weather.

'If you've got really crap weather for two weeks and a ship's bouncing around, your cabin's rearranging itself, you do not sleep very well. And that has an accumulative effect'

For those who went home between shifts, the time spent travelling plus the demands of home life had an impact on the time available for sleep, as well as introducing a risk of falling asleep during the commute. The commute time was also a factor for those live-onboard crew who had a long commute before starting their first shift.

'A major factor is arriving to the ship after being up early morn, travelling and then straight into your working shift'

'So even though we've got our 12 hours, we don't because we're travelling at least a good hour and a half sometimes'

'I would drive home after an early shift ... One instance saw me "fall asleep" at the wheel nearing home, fortunately for me I woke up at the corner with a lorry approaching from the other direction'

Task-related fatigue: In addition to the impact of lost sleep, task-related fatigue also occurs due to the physical demands of the job, including looking after passengers, frequent running up and down stairs (often in safety shoes/clothing) and securing lorries on the vehicle decks.

'Just imagine, if you can, that three persons in bad weather need to apply for 70 units, 4 chains and 4 turnbuckles, altogether 280 of each, carrying an impact wrench all the time. And 6 hours later to take them off. And to do that two times a day, crouching under the trailers during wind, rain, cold and hot weather, with weight of personal equipment of 25 kg'

'Another thing that I'd say is, a lot of stress and tiredness is angry … abusive passengers because we get a lot of that as well'

Seafaring culture can contribute to fatigue

Many research participants considered that fatigue was integral to the industry. Challenging this culture could be difficult, as to report fatigue or request help when tired would, they felt, be perceived as a sign of weakness amongst peers.

'I think it's always been just an accepted thing in the industry, that people are just tired on ships. … because it is a 24-hour industry, you're awake when the ship needs you'

'I feel like you'd be laughed at'

However, there was also evidence of senior crew recognising and managing fatigue. For example, several masters had taken a decision to delay or cancel sailings when they felt the crew were too tired to sail. Also, some participants in focus groups talked about feeling like part of a family and were confident that they could rely on their colleagues to help them out if they were struggling. Nevertheless, they still considered that fatigue was an inevitable part of the job.

'It had been such a rough night and we were doing four knots ... just not going anywhere. And by the time we got back, we were all knackered. And he [the master] said, "We're not going anywhere"'

'We're like a second family on here … everybody would come … to help out with whatever situation you were in'

Very few interviewees and focus group participants had received any training about fatigue management and only 8% of survey respondents reported having had such training. As a result, they had limited knowledge of good fatigue management practices. For example, there was widespread use of caffeine as a fatigue control measure (which is effective in the short term, but not a substitute for good fatigue management), and many survey respondents also reported using measures such as going out on deck or listening to music. There is no good evidence that these are effective ways of controlling fatigue, particularly when it is related to inadequate sleep or circadian rhythm effects.

'The shift runs on coffee'

There appears to be a lack of information at an industry and company level to support good decision making about fatigue. Only 35% of survey respondents felt they were always able to record their rest/work hours accurately.

Some things that were not found, and why

One of the aims of this research was to identify whether seafarers in particular roles or working particular shift patterns were at higher risk of fatigue. The survey showed that service crew were more at risk of fatigue than those in other roles. They were the most likely to have tiredness every day and reported the worst sleep.

However, we found no major differences between job roles regarding sleepiness whilst on duty or from other research activities. Also, we did not find significant differences in fatigue between different rosters or schedules. This may be because there was such a wide range of different roster/shift patterns reported; also that many other factors were affecting fatigue. It is not evidence that these differences do not exist.

Recommendations for better fatigue management

Although fatigue management in ferry operations is not easy, fatigue is influenced by many contributing factors and is not inevitable. The following are important steps which all operators should consider:

Develop fatigue risk management programmes. This would increase focus on fatigue, highlight that it is a serious issue and promote discussion.

Provide education for all on fatigue management. Specific training should also be provided consistently across the ferry sector for those with responsibilities for managing fatigue in others.

Maximise the available time for sleep for all crew. Avoid variability in shifts, changes to planned shifts, and disturbing crew during rest hours. Design shift patterns to minimise impact on circadian rhythm.

Gather accurate information. Ensure the hours actually worked are recorded, and identify all occasions when fatigue contributes to incidents or near misses.

Develop a fatigue-aware culture. Encourage crew at all levels to recognise fatigue, to report it, and to be supportive when others report it.

Read the full report

The Loughborough University fatigue paper is based on research carried out by Wendy Jones, Ashleigh Filtness, Anna Sjors Dahlman, Sally Maynard, Adam Asmal, Andrew Pooley, Christer Ahlstrom and Anna Anund.

The project was publicised in the Nautilus Telegraph and on the Union's website, so some participants in the survey and focus groups are likely to have been Nautilus members.

Tags

More articles

Seafarer fatigue: the weary weight of evidence

Fatigue: Another 'Inconvenient Truth'

Project Horizon

The findings of the fatigue study as part of the Project Horizon campaign – a multi-partner research initiative to investigate the impact of watchkeeping patterns on the cognitive performance of seafarers.