- Topics

- Campaigning

- Careers

- Colleges

- Community

- Education and training

- Environment

- Equality

- Federation

- General secretary message

- Government

- Health and safety

- History

- Industrial

- International

- Law

- Members at work

- Nautilus news

- Nautilus partnerships

- Netherlands

- Open days

- Opinion

- Organising

- Podcasts from Nautilus

- Sponsored content

- Switzerland

- Technology

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom

- Welfare

A major project to update the shipping industry's guidelines on preventing seafarer fatigue has come to an end. Will it make a difference? ANDREW LININGTON reports

Global guidelines to combat seafarer fatigue have been revised for the first time in 17 years following a major International Maritime Organisation (IMO) review.

An expert working group spent almost four years updating the IMO guidance on fatigue mitigation and management, to reflect the results of recent research into the problems – such as the Project Horizon study published in 2012.

Nautilus professional and technical officer David Appleton attended the IMO human element, training and watchkeeping sub-committee meeting called to approve the new guidelines, which will now go to the maritime safety committee for final approval in December.

'Overall, the new guidance is better than what we had before – but it is not in any way what would be considered sufficient in any other industry, and it is clear that a culture change is required in shipping,' he said.

There was some heated debate at the IMO meeting over the use of fatigue risk management tools and evidence-based points in helping to determine work patterns, Mr Appleton noted. Some delegations argued that advice to avoid working more than 70 hours a week or regularly working more than 12 hours a day conflicted with what the working time regulations actually permit.

'To have that as guidance does not mean you can't work more than 12 hours a day, but it does mean you should take it into account as a risk factor and take action to mitigate its effects when there is a solid body of research to show that working to the limits and beyond is not safe,' Mr Appleton pointed out.

'The regulations set maximum permissible limits; they do not represent best practice and nor should they serve as targets for the industry.'

Among the studies considered by the working group was a report from the Australian Maritime Safety Authority presenting the findings of research into seafarer safety and wellbeing carried out in collaboration with the universities of Queensland and Western Australia.

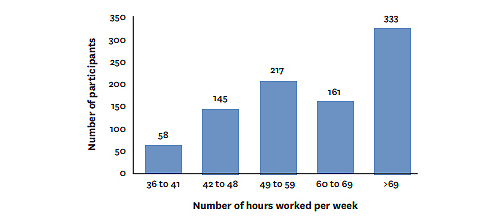

Almost 30% of the 1,026 seafarers taking part in the study reported working more than 69 hours a week and, on average, they were clocking up 61.28 hours of work a week. Almost 20% said they experienced chronic fatigue, and around 20% suffered high levels of acute fatigue.

'The combination of job insecurity and long working hours, in uncertain operational conditions, while required to maintain high levels of vigilance resulted in seafarers experiencing increased sleep problems,' the report states.

Around 12% of the seafarers complained of sleep problems, with more than one in five describing their working hours as unpredictable. A similar proportion also pointed to the problems caused by ship motion and loud noise onboard.

The report notes the links between long working hours and mental ill health, sleep problems and near-misses and injuries.

Around 40% of the seafarers surveyed said they experienced symptoms of mental ill health, such as depression and anxiety, and around 10% said they experienced these symptoms often.

The study adds to the findings of research such as the EU-funded Project Horizon in demonstrating the way in which the current work rest regulations do not provide seafarers with adequate protection against fatigue – with the six-on/six-off pattern in particular failing to set aside sufficient rest time for sleep and recovery. 'Work schedules that do not allow for adequate sleep lead to sleep debt,' it points out. 'Sleep debt, especially across a number of days, leads to changes in employees' immune system, psychological functioning and mental wellbeing.'

Researchers also identified the high demand on seafarers to be vigilant while at work, stressing that this can contribute to fatigue, incomplete recovery between shifts and reduced quality of sleep.

Seafarers' sleep problems are also influenced by factors such as work-related pressures and the safety leadership behaviour of superiors, the report notes.

The researchers found that levels of fatigue at the end of a duty period or workday could be 'markedly alleviated' by such things as seafarers being given autonomy, trust and high levels of job security, as well as not working in dirty, hazardous and confined spaces.

'However,' the report concludes, 'with increasingly less stable crews, reduced job security and increased diversity of crews, these quality, trusting and supporting social processes onboard the ships might be impaired.'

Against this background, the report argues,' an effective fatigue management system that continuously monitors and manages the risk of fatigue is essential'.

It also points to some 'easily implementable' measures to improve crew accommodation, such as more comfortable mattresses, blackout curtains and noise reduction.

As well as proactive policies, the report says there is a need for reactive interventions to minimise the effects of fatigue-related problems once they have occurred.

These should include onboard reporting mechanisms, clear policies for helping seafarers with sleep problems, and employee assistance programmes to provide psychological and psychosocial counselling.

The revised IMO guidelines seek to address these issues by providing information on the causes and consequences of fatigue, and the risks it poses to the safety and health of seafarers, operational safety, security and protection of the marine environment.

The guidelines are aimed not just at shipping companies, but also at seafarers, maritime administrations, naval architects/ ship designers and training providers. Flag states and shipping companies will be advised to take them into consideration when determining minimum safe manning, and to take the issue of fatigue into account when developing, implementing and improving safety management systems under the ISM Code.

The new guidelines are composed of six modules and two annexes – with each module addressing a particular stakeholder group within the maritime industry. The modules cover:fatigue; fatigue and the company; fatigue and the seafarer; fatigue, awareness and training; fatigue and ship design; and fatigue, the administration and port state authorities.

The annexes provide examples of sleep and fatigue monitoring tools and an example of a fatigue event report information.

'We certainly do not see this as being the end of the matter,' Mr Appleton said. 'Risk management tools to support guidelines on fatigue will be considered as a standing agenda item in the future, and that will provide further opportunities to improve the situation.'

Sleep debt leads to changes in employees' immune systems, psychological functioning and mental wellbeing

Fine for fatigue

Maritime safety officials in New Zealand have warned operators to guard against fatigue after an owner was fined NZ$27,200 (€15,600) following the loss of a fishing vessel after the watchkeeper fell asleep.

A court heard that the seafarer had worked a full day and had less than two hours of sleep before taking over the watch in the early hours of 11 January 2016. The vessel, pictured, grounded on rocks and capsized in the Bay of Islands after he fell asleep.

Maritime NZ Northern regional manager Neil Rowarth said it was a matter of luck that no one had died in the accident and the prosecution of the owners sent a strong message to all maritime operators that they must have an effective system for managing crew fatigue.

A recent Maritime NZ survey found that 61% of commercial fishing crew reported working when overtired and more than one-third had fallen asleep on watch.

Tags