- Topics

- Campaigning

- Careers

- Colleges

- Community

- Education and training

- Environment

- Equality

- Federation

- General secretary message

- Government

- Health and safety

- History

- Industrial

- International

- Law

- Members at work

- Nautilus news

- Nautilus partnerships

- Netherlands

- Open days

- Opinion

- Organising

- Podcasts from Nautilus

- Sponsored content

- Switzerland

- Technology

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom

- Welfare

The future of forecasts – why shipping needs to improve its weather data to take account of climate change

20 February 2020

We all like a good moan about the weather. But seafarers have more reason than most to have concerns about the impact of climate change, and those worries are now being heard at the highest levels. Andrew Linington reports

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) have recently launched a joint initiative to examine the threat posed by increasingly extreme weather conditions at sea and to improve the quality of forecasts provided to ships.

Marine insurance statistics show that weather is the cause of some 30% of all ship losses. A vessel operating in winds of Beaufort 8 or greater for more than 1.5% of the time will have a 31% greater chance of a 'Particular Average' insurance claim, excluding machinery claims, and a 29% extra chance of a crew injury claim.

Bad weather not only increases the risk of seafarers having accidents, but also has a significant impact on crew fatigue. It can cause fuel issues and raises long-term concerns over ship design and maintenance.

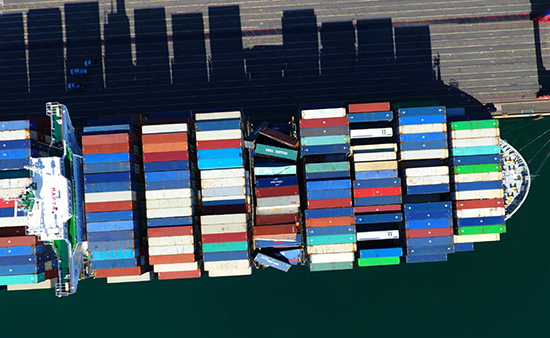

The insurers' figures also show that the proportion of accidents linked to weather has increased steadily over the past 15 years, with incidents including hull damage, cargo and machinery damage, containers lost overboard, water damage and leaking hatches, loss of vessel stability and parametric rolling – the latter most recently highlighted in a UK Marine Investigation Branch (MAIB) report on the collapse of three container bays and loss of 137 containers from the CMA CGM G.Washington during heavy weather in the Pacific in January 2018.

Good data on wave heights is hard to find, but the evidence broadly suggests that wave energy is growing and increases in wind speeds and wave heights are evident in localised areas of the ocean in the high latitudes of both hemispheres.

At the same time, the 'super-sizing' of many ship types has increased their exposure to the effects of wind. A 30 knot wind against the 16,000 sq m of a large containership is equivalent to more than 300 tonnes of bollard pull, or more than 200 tonnes at 35 knots for a large cruiseship where conventional thrusters can only handle up to 150 tonnes.

Nautilus member and passengership master Captain Nick Nash says he has witnessed the results of climate change during the past couple of decades. 'I have noticed that winds are generally increasing,' he told the Telegraph. 'The average daytime wind in the Caribbean, for example, has increased from 20 knots to 25 knots over the last 20 years that I have been sailing there. Hurricane frequency seems to be up – but that may be due to better forecasting.

'Looking at England, winter storms and severity have increased,' he noted. 'It would be interesting to see what effect this increased bad weather has had on the Channel ferries in and out of Dover.'

Capt Nash told the recent IMO/WMO conference on climate change that large-sided vessels such as cruiseships, ferries and containerships are particularly exposed to the effects of side winds when manoeuvring in port. 'A 5 knot increase may not be much for a forecaster, but it is very significant for us,' he pointed out.

'We need accurate real-time wind information from inside the port and critical areas in the approach channel to enable "go/no-go" decisions to be made in ample time,' he added.

'Accurate 10m and, say, 60m forecasts are also needed – some shipping companies do supply these (Princess for one) and they assist greatly,' Capt Nash pointed out. 'Local port forecasts by a local meteorologist (not using a model) are also very helpful.'

Changing climate effects are causing particular concern to pilots and port authorities, with the World Association for Waterborne Transport Infrastructure (PIANC) leading a nine-member project that is examining ways for ports and harbours to strengthen resilience and mitigate the effects of more extreme conditions.

Nick Cutmore, secretary-general of the International Maritime Pilots' Association, told PIANC's first Navigating a Changing Climate conference about the challenges of piloting increasingly larger ships at a time of rising sea levels, storm surges, rainfall and river flows (both increasing and decreasing) and fog. 'Working with nature that is always changing, sometimes very suddenly, requires understanding, learning and respect for the environment – including weather and climate,' he pointed out.

Partly in response to climate change, more and more ships are now operating in polar regions, raising particular concerns about the challenges of gaining accurate ice information. The International Ice Charting Working Group (IICWG) recently surveyed seafarers about their satisfaction with ice information and their needs in a fast-changing polar environment.

The need for more reliable forecasts was repeatedly stressed during the IMO/WMO symposium. 'There's a need for a greater understanding and awareness of the benefits that met-ocean data can provide to the mariner on a day-to-day basis,' Nick Cutmore noted. 'Similarly, the met-ocean community needs greater awareness of the kinds of decisions that mariners must make.'

Experts say that met-ocean forecasting technologies are advancing rapidly, providing greater accuracy and more timely warnings. 'We must apply the gains we've made in science, observing, computing, and communications to bring relevant 21st century services to the maritime community,' said symposium chair Tom Cuff of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

However, the meeting was reminded of the shocking loss of the US-flagged containership El Faro when it sailed into the path of a category 3 hurricane in October 2015. Investigations revealed the vessel was relying on non-current weather information, and this resulted in the launch of a task force to investigate the impact of extreme weather events on shipping.

The task force called for improvements in weather information and seafarer training (including a review of deck officer training to determine if extreme storm response sections should be modified or enhanced), as well as better definition of the terms 'heavy weather' and 'extreme' weather. It proposed further work to develop standards for ECDIS weather overlays to modernise the dissemination of critical weather information direct to ships' navigation systems.

Met-ocean service providers are also being asked to look at ways of adapting their forecasts to give a better definition of the impacts of the weather on shipping – moving from the approach of explaining what the weather will be to what the weather will actually do. This could include refined information about the impacts of weather on port infrastructure and vessels at berth, and accessible real time information from ports and harbours before vessels approach them.

Met-ocean service providers are being asked to forecast the impacts of the weather on shipping ‒ moving from explaining what the weather will be to what it will actually do

The US report also stressed the importance of increasing the number and quality of weather observation reports from ships – something that the IMO and WMO are seeking to focus on. Former International Chamber of Shipping secretary-general Peter Hinchliffe warned that a 'shockingly small' number of ships provide met data.

The SOLAS Convention encourages companies and mariners to report weather observations at sea, providing vital information about such things as atmospheric pressure, wind speed and direction, waves and swell, sea ice, and fog.

Emma Steventon of the UK Met Office said such reports give forecasters vital real-time feedback on ocean weather conditions which can help to improve the quality of forecasts and warnings issued, as well as providing essential information for ship routeing and search and rescue services, and important data to help climate change research.

However, comparisons between AIS plots of vessels against real time shipboard weather reports indicate that few ships participate in providing observations for use by national meteorological services. The WMO's voluntary observation scheme, consisting of 29 countries, recently reported that just 15% of commercial vessels actively participate in the programme.

For marine forecasters, the paucity of accurate information from ships at sea means that they have to rely heavily on remotely sensed data from geostationary and low earth orbiting satellites. This presents some serious limitations – for example, ice is not always detectable by satellite.

Improving the supply of quality data on the reality of at-sea conditions will also help to enhance the safety of ship design, with accurate information about wave patterns and significant wave heights being crucial to the development of classification society calculations for wave bending moments and acceptable pressures on deck plates and hatch covers, for instance.

Authorities are looking at ways in which more ships can be encouraged to take part in observation reporting schemes. They want to ensure that seafarers fully appreciate the impact and value of shipboard observations in improving the quality and accuracy of met-ocean forecasts – as well as helping to monitor the wider climate and ocean health at a time of growing environmental sensitivities.

There are even suggestions that the data collection gap could be bridged by amending the SOLAS Convention to introduce regulations that would require ships to collect and share observations. Alternatively, it has also been argued that flag states should ensure that a set percentage of their fleets should regularly report observations, or that authorities should make more use of AIS data to enhance situational awareness about weather avoidance practices by ships and to give forecasters the ability to better understand the impacts of heavy and extreme weather on marine operations.

Capt Nash said that there are some good, free, websites – such as Windfinder, AccuWeather and Windy – to provide additional information for ships. However, he stressed, there is a need for official accreditation by the WMO to indicate the accuracy and reliability of such services.

He added: 'I love this quote: "The trouble with weather forecasting is that its right too often for us to ignore it, but wrong too often for us to rely on it!"

Tags