Trevessa

The build

Built in 1909 as the German ship Imkenturm, the 5,004grt Trevessa had been bought by the Hain Steamship Company of Cornwall in 1920 after being taken as a ‘war prize’ by the British Ministry of Shipping.

Abandon ship

On 25 May 1923 Trevessa departed from Fremantle, Western Australia, bound for London and Antwerp after loading a cargo of zinc concentrates at Port Pirie. Ten days later, some 1,640 miles from the Australian coast, the crew were forced to abandon ship when it started to sink after taking on water in gale force conditions.

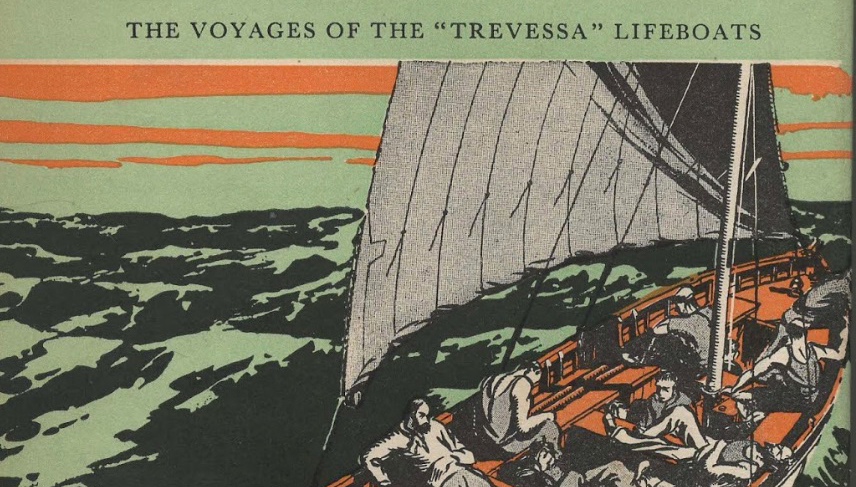

The seafarers managed to get into two 26ft lifeboats – one commanded by the master, Captain Cecil Foster, and the other by the chief officer, James Smith. After making a final check of charts on the bridge, Capt Foster had decided that they should head for Mauritius, some 1,700 miles away.

Each boat was stocked with 550 biscuits, 130 tins of condensed milk and around 15 gallons of water and Capt Foster calculated that by rationing each man to one biscuit, four teaspoonfuls of milk, and around three tablespoonfuls of water each day they could last out the estimated three-week voyage to Mauritius.

Although they had hoped to sail together, the men soon discovered that Capt. Foster’s boat was faster, and they decided that ‘each boat should make the best of it and reach land as soon as was possible’.

Survival

There was no chart in the master’s boat and the officers navigated with the aid of the stars and the sun and by the direction in which the sea was running. They had no chronometers, and the survivors described the spirit compasses on the boats as being of little use because they were too slow in their movement.

In the searing heat the men quickly experienced the effects of hunger, thirst, and exposure, finding it increasingly difficult to use the oars. Some of them struggled to eat the dry biscuits, although they managed to supplement their water supplies by catching rainwater in cigarette tins.

During their time at sea, nine of the men died due to exhaustion, exposure and drinking sea water, while an engineer officer fell overboard and drowned, and a cook died soon after they reached land.

Capt. Foster – who had twice survived in lifeboats after his ships were torpedoed in the First World War – was able to use his experience to help others, offering suggestions such as sucking buttons to keep their mouths moist.

Keeping up morale

He managed to maintain morale by leading the singing of ‘sea ditties’, organising the men into watches and giving them duties such as rowing or managing the sail, doing repairs and baling out, or keeping a lookout for land or ships. Food and drink were shared out at fixed intervals, to enable everyone to see they were getting equal amounts.

After almost three weeks at sea, spirits rose when a bosun bird was spotted flying near Capt. Foster’s boat – suggesting they were nearing land – and 22 days and 19 hours and 1,556 miles after their ship sank, the boat reached Rodrigues Island, some 350 miles east of Mauritius. The chief officer’s boat arrived in Souillac, southern Mauritius just two days later, having covered 1,747 miles.

Outstanding seamanship

Back home, hopes that the men had survived had faded when ships searching for them found only wreckage. When news of their survival reached Britain, the men were rapidly hailed as heroes. On their return to London, Capt. Foster and chief officer Smith were asked to visit Buckingham Palace and both were awarded the Lloyd’s silver medal ‘in recognition of this outstanding feat of seamanship’.

Public appeal and Nautilus

Nautilus International’s predecessor union, the Imperial Merchant Service Guild, contributed 10 guineas to a public appeal which raised £1,442 for the crew and also represented Capt. Foster during an inquiry into the loss. Although the master was cleared of any blame for the loss, he never returned to sea.

What was described by one newspaper as ‘The Great Adventure that will live in memory the world over’ also left some other legacies – prompting a political storm over the practice of stopping seafarers’ pay as soon as a ship sank, sparking a debate about the carriage of wireless equipment in lifeboats, and leading – in 1925 – to the introduction of regulations requiring supplies of condensed milk on lifeboats.

Contribute

Are you knowledgeable about this vessel?

Submit your contribution to this article to our editorial team.

Write to usView more ships of the past

HMS Beagle

Launched 200 years ago, HMS Beagle has been described as one of the most important ships in history – thanks to the observations on evolution and natural selection that its famous passenger Charles Darwin made during a five-year voyage around the world between 1831 and 1836.

Common.ReadMoreHMS Beagle

Prinsendam

Entering into service in November 1973 – Holland America Line's centenary year – the 8,566gt Prinsendam was the last cruiseship to be built in a Dutch shipyard. However, its career was cut short by a devastating fire in 1980.

Common.ReadMorePrinsendam

Nicola

Launched in December 1967 at the Austin & Pickersgill (A&P) yard in Sunderland, the 9,034grt general cargoship Nicola was the first in a series of more than 200 British-designed vessels intended to replace the 'cheap and cheerful' Liberty ships built by the US during the Second World War.

Common.ReadMore